Expanding My Clinical Lens: Insights Gained From Rural Healthcare in Honduras

My Medical Missions Trip

I always dreamed of studying abroad, yet every year I found a reason not to go, either I was too busy, or the trip was too expensive. This past summer, after hearing the advice to “make the most of your last summer,” I stopped making excuses and finally committed to a medical mission trip to Honduras. What I did not expect was how profoundly it would reshape my perspective on the responsibility that comes with wearing a white coat.

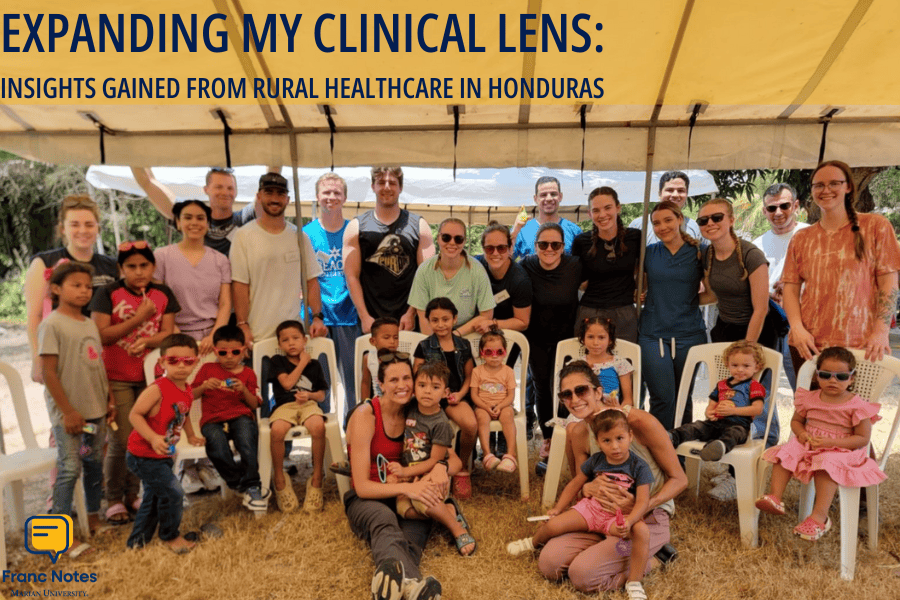

Our team was composed of doctors and nurses from Ascencion St. Vincent, medical students from Marian, and translators and administrators from Humanity and Hope. We provided healthcare to five villages nestled in rural areas of Honduras.

Each day, we worked to transform community centers and schools into makeshift clinics and pharmacies. Designated tents became stations for triage, history taking, and vitals. After setting up, we began with an education seminar for both the adults and children of the community. Residents learned about hypertension, diabetes, lung and skin cancer prevention, while the children’s session was focused on emotional expression. In these communities, knowledge was just as impactful as any medication we could offer. As medical students, we went to our assigned tent to complete registrations, take vitals and histories, present to the residents and attendings, and help distribute prescribed medications.

The scenery was breathtaking, yet the isolation was striking. Many residents lived hours away from the hospital, making our presence that much more impactful. Serving in these rural communities posed logistical challenges—some days requiring multiple hour-long bus rides, mountain treks, or even crossing suspension bridges to reach patients. While barriers like geography and poverty cannot be solved with a single clinic day, our small interventions had the power to change someone’s life.

I witnessed it firsthand when an adolescent female visited our clinic. She suffered from a urinary tract infection that caused tremendous abdominal pain and left her unable to work. I continued to ask if other activities worsened the pain, and her face fell. She explained that she had not been able to do anything besides staying home. Her somberness displayed her growing feelings of isolation and hopelessness. She was breastfeeding at the time, so the physician and I had to consider this regarding her medications and treatment plan. We prescribed an appropriate antibiotic and provided the patient with education concerning proper hygiene practices. What seemed like simple advice to me meant the difference between recurring illness and restored hope. In these communities, education was not a supplement but rather transformative, shaping not only health but emotional and economic well-being.

I witnessed it firsthand when an adolescent female visited our clinic. She suffered from a urinary tract infection that caused tremendous abdominal pain and left her unable to work. I continued to ask if other activities worsened the pain, and her face fell. She explained that she had not been able to do anything besides staying home. Her somberness displayed her growing feelings of isolation and hopelessness. She was breastfeeding at the time, so the physician and I had to consider this regarding her medications and treatment plan. We prescribed an appropriate antibiotic and provided the patient with education concerning proper hygiene practices. What seemed like simple advice to me meant the difference between recurring illness and restored hope. In these communities, education was not a supplement but rather transformative, shaping not only health but emotional and economic well-being.

Each clinical station felt familiar, echoing responsibilities I had practiced and observed in my home clinic. However, the experience quickly deepened as I learned to look beyond the chief complaint. When a male patient presented with abdominal pain, I applied the framework we learned in class, asking about the location, duration, and severity of the pain. I felt confident in my approach—until I listened to the physician ask about bowel habits and dietary changes, things I had overlooked. This patient had taught me that a complete history is more than a checklist, but rather a foundation for a sound differential. I realized how easy it is to anchor on the obvious and overlook contributing factors. By the end of the week, I was beginning to ask more target follow-ups, piecing together patterns, and thinking beyond one organ system. Each oversight became a lesson, sharpening my clinical reasoning and reinforcing my appreciation for the art of questioning. I left Honduras with the valuable lesson that sometimes the questions we overlook can be the key to the right diagnosis.

In Summary

I was reminded that sometimes the most powerful impact we can make is not through complex interventions, but through simple conversations—asking the right questions, offering practical education, and showing we care. It is about seeing the patient as a whole person that is shaped by their environment, knowledge, and access to care. We were strangers in these communities, yet they welcomed us with gratitude and trust before we even began. This confidence in our team reinforced something profound. The white coat not only signifies knowledge, but it also carries expectations of compassion, problem-solving, and education. It positions us as sympathetic caregivers, investigators, and teachers, a symbol that transcends geographical boundaries.

To anyone considering a medical mission, I wholeheartedly encourage you to take the leap. It is not just an opportunity to serve others, but a powerful step toward becoming a more empathetic and well-rounded medical provider. I’ll carry with me the lessons of this mission that healing is not just prescribing, but empowering and teaching.

For me, Honduras was a defining experience, where I came to see the white coat differently, not as an achievement, but as a commitment. One that extends beyond borders and one I am ready to live up to.

About the Author

Megan Titus is a second-year osteopathic medical student attending the Marian University Tom and Julie Wood College of Osteopathic Medicine. Originally from Michigan, she loves to spend her free time by the water, whether boating, swimming, fishing, or simply relaxing. She is currently interested in pediatrics and obstetrics but is excited to explore a variety of specialties. Megan would like to thank you for taking the time to read about her trip!

Megan Titus is a second-year osteopathic medical student attending the Marian University Tom and Julie Wood College of Osteopathic Medicine. Originally from Michigan, she loves to spend her free time by the water, whether boating, swimming, fishing, or simply relaxing. She is currently interested in pediatrics and obstetrics but is excited to explore a variety of specialties. Megan would like to thank you for taking the time to read about her trip!

About Franc Notes

Discover the voices of Marian University's health professions students through "Franc Notes", a vibrant, student-led blog that embodies our Franciscan commitment to community, reflection, and compassionate service. Inspired by the rhythm of "SOAP notes," it features weekly insights—from "DO Diaries" interviews with physicians to summer reflections and program spotlights—fostering collaboration across disciplines."